CONTEMPORARY INTERIOR

SIBERIA | NOV 2020

THE VIOLINIST

IS STILL NECESSARY

BORN IN NOVOSIBIRSK IN 1959, IVAN SHALMIN LIVES AND WORKS IN MOSCOW. HE STUDIED ARCHITECTURE WITHIN THE TOWN PLANNING FACULTY AT KYIBISHEV NISI (NOVOSIBIRSK INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION). OVER THE LAST 20 YEARS HE HAS DESIGNED AND BUILT (WITH ASSISTANCE) MORE THAN 70 ARCHITECTURAL AND INTERIOR DESIGN PROJECTS.

In 2016, Ivan began to create digital paintings. Currently, he is overseeing the final stages and the finishing works for two of his latest projects - a villa called ‘Ghost’ and the Strotskis cluster, containing offices, 145 000 sqm of flats and a business centre. In 2020 also he held his first solo exhibitions of art and architecture in Moscow and Novosibirsk.

We are interviewing Ivan in Moscow’s main postal building - ‘Pochta Rossii’ or ‘Post of Russia’, situated on the Varshavskoye highway. Due to lockdown, there have been difficulties with purchasing furniture, accessories, various servicing parts and even simple LEDs. Ivan needs very specific types of lamps, to create the right lighting conditions within his interiors, so he is forced to order them online. The customs section within this large building is not the best place to conduct an interview; but this location also gives us an advantage, as we are able to find out a lot more detail about routine tasks, characteristic to Ivan’s profession. We talk about custom architectural projects in general and then switch to specific recent works.

‘Ghost’ is not the first villa that Ivan has designed and built for the same client. ‘It’s probably the 6th one’ he says, appearing to have lost count. Their working relationship began with a simple consultation about a kitchen within a property that was already in the final stages of its construction. Despite the fact that the windows had already been installed, this consultation ended with three quarters of the property demolished, redesigned and rebuilt. ‘After that I have built another few houses for them. It’s their style. They like to build a villa, stay in it for a few years, sell it on, and then build a new one. This is the ideal client. They hardly ever interfere with the creative process and the most important thing is that they are not afraid to take risks if I offer new ideas. It’s interesting to work with them. Although sometimes they too start to ‘tighten the screws’. When this happens, the answer is simple, but effective ‘I will never create anything substandard, so if you want a high quality product, you have to trust the architect and do as he says.’ – explains Ivan using much stronger expletives.

Most of the projects built for this client are situated in Ryblveka, on the outskirts of Moscow, but there was also a house in Antibes (a small town in Provence, France). Here, the client bought a rundown villa, called ‘Segal’ (or ‘cricket’, in French); designed and built by an Italian architect over 100 years ago. The building was in urgent need of restoration and Ivan took on the reconstruction. He increased the area of the villa by two thirds, up to 350 sqm (the key requirement was to meet the local building regulations, that is for the building area to be below 27% of the surrounding lands). Originally, the villa consisted of a series of terraces and Ivan’s key move was to glaze them. He also designed a swimming pool, specifically positioned to have a view out to sea through the volume of the building. Segal is a second-line coastal property and the exit to the sea is marked with a memorial plaque to Claude Monet, as this is where the artist had painted a series of works depicting Antibes. ‘This story has influenced the appearance of the interior, where it was only possible to hang works by Claude Monet.’ – explains the architect.

Currently, the profession of the architect is stagnating, because most of the time, the architect has become ‘subservient’ to the builder. If the builder can negotiate directly with the client, there’s no point in working there. But if you have the ability to create a kingdom within a kingdom, so to speak on the building site, if you can organise the process in such a way that people will listen to you, then your presence is worthwhile. People only understand the language of money, so the key thing is to position yourself in such a way that the builders can only get paid through you. Then and only then will there be a reason for the architect to be there, and the violinist will indeed be necessary (‘The violinist is necessary’ is a reference to a Soviet dystopian sci-fi film, ‘Kin-dza-dza’ – one of Ivan’s favourites).

Buried deep in Ivan’s archives is a project called ‘The Bastion of Resistance’. ‘Back then, together with Kostiya Vronskiy (architect Konstantin Vronskiy) we formulated a concept, in the form of a short text: ‘All his life, man builds himself walls. These very walls ruin his life but at the same time, he cannot live without them.’ Allegoriaclly, the wall signifies the rules that inhibit our freedom. Everyone wants to be behind the wall, or rather, on the other side of it. ‘Ghost’ is a manifestation of this concept. The south wall, consisting of clinker brick is almost completely impermeable. Integrated into this wall is a glass fragment that symbolises the beginning of its destruction and therefore freedom from rules and boundaries. The opposite wall is almost entirely made of glass, with a small inset of a brick wall fragment, symbolising wreckage. This is a demonstration of the total disappearance of boundaries.’ – explains Ivan about the concept.

Almost all of his buildings use a Belgian tinted ‘en masse’ glass, called ‘Planibel Grey’ and it becomes apparent that this is one of the his favourite materials. ‘When the light shines onto it directly, this glass works like a one way mirror or, in other lighting conditions, it becomes almost invisible. Planibel Grey also has filtering properties and increases the sharpness of whatever is behind it. This way, the surroundings quite literally become clearer and brighter. The daily change and play between light and shadow, combined with this glass makes the house appear to be invisible, or ghost like. Due to the properties of this specialist glass, the villa changes from having weight and mass to losing it, from resembling a mirror to dissolving almost completely into its surroundings.’

Ivan has a very specific attitude to space and that is always apparent in his projects. ‘The architect is always designing the hole within the bagel. Jeltovskiy had once said: ‘To draw a beautiful balustrade, you must draw the space between the balusters.’ We as architects, operate within orthogonal projections but they are nominal and perception always works best in perspective. I constantly aim to blur the boundaries between the internal and the external. Also, it’s very important to see the project through to completion, to be its composer right up until the client moves in.’

One of Ivan’s signature design details are his swimming pools. They are called ‘solid water’. This effect is achieved by lifting the water plane 25 cm above ground level and using simple transparent ledges. This way the water appears to be ‘solid’.

The first ‘solid water’ pool was designed for a client in Spain at the beginning of 2000s. It was clad with black tiles and had acrylic ledges. ‘The black basin looks like a mirror. If you are swimming at night, it looks like you are swimming amongst the stars, in nature. The first pool like this was made for a villa called ‘Propylaeum’ on the outskirts of Moscow. Today, there are more than ten ‘solid water’ swimming pools and each one is positioned differently within the building. The very first one, is right in the centre, and due to the illusion created by the transparent ledges, the whole space appears to be flooded with water. In another villa, the pool is shifted away to the side, to make room for some chaise longues. ‘Ghost’ also has a ‘hard water’ swimming pool. Although there is a different illusion here, it looks like the swimming pool continues beyond the building and spills out onto the surrounding grounds. The structural glass strengthens the sensation of weightlessness and the absence of walls in this space. It appears as though the wooden ceiling is floating above the pool with no loadbearing elements underneath.

I AM ALWAYS AGAINST ANY STANDARDISED PROJECTS.

For this ‘ideal’ client, Ivan has also built a villa called ‘Dinosaur’. He has a great naming approach - there’s also ‘Glabrous’, ‘Propylaeum’ and ‘ the Rugged’. ‘These names are significant because they always contain the key concept behind the project,’ says Ivan. Even if the villas get sold, they almost never get modified. The houses built by Ivan are objects in their own right, physical thought forms, manifestations of conceptual thinking.

‘The classic argument in architecture between the importance of form over function, the content and its container has no place to be, so long as the building is formulated by a strong, and fully crystallized concept.’ – says Ivan. ‘If the form and the function are fully integrated into one another, the building will stand the test of time and remain unchanged, even as a museum. A great example of this is the Lenin mausoleum by architect Shusev. There is actually a competition running at the present moment to repurpose this mausoleum. However, the building is so laconic and so well established with its own distinct associations, that its very difficult to imagine it serving a different purpose, other than a museum about the creation of itself.’

Consequently, this is also the answer to the question of the industrialization of custom architectural projects. According to Ivan, these standardised projects can only ever be designed for what he calls short or temporary stays – hotels, hospitals, etc. But the standard project can never cater to individual needs. ‘It’s a western idea to build individual projects on an industrial scale. By the way, the first American homes utilized soviet plywood, as it was very durable. Here in Russia, it was always the other way round. The commission came from the government, including the production of panels. First, they built five-storey homes, but then the buildings grew much taller. And so, the style of the masses was cultivated. Just like in ‘Kin-dza-dza’ – ‘the violinist is unnecessary’, the architect was only getting in the way, disrupting the work of the builders. After all, the builder always knows how to make the structure really durable. Here, the famous triad of Vitruvius - ‘utility, durability and beauty’ is broken. If you take one of these constituents away, the architecture loses its meaning because it ceases to be an art form’ – explains Ivan with a hint of irony.

The architect thinks that even in our country, everyone can afford to live according to this rule. Everyone understands beauty, although they perceive it on more of an emotional level. It’s easy to assume that this ability is also dependent on your level of income but Ivan disagrees. He wisely points out, that even on a limited budget, the architect can still create something beautiful, functional and durable. And budget is therefore not the main deciding factor when it comes to choosing whether to work with an architect or not.

‘The role of the architect is to find the one and only appropriate solution in order for the client to build exactly what he needs. I like Phillipe Stark’s approach – cheap and even disposable objects should also be beautiful. I am against any standardised projects. Even though I do have a series of houses that look alike, they are similar in structure and use similar cladding materials, but they are still very different. We need to remember that we are not building the bagle itself here but the hole in the middle of the bagle, creating a space fit for living.’ – says Ivan with conviction.

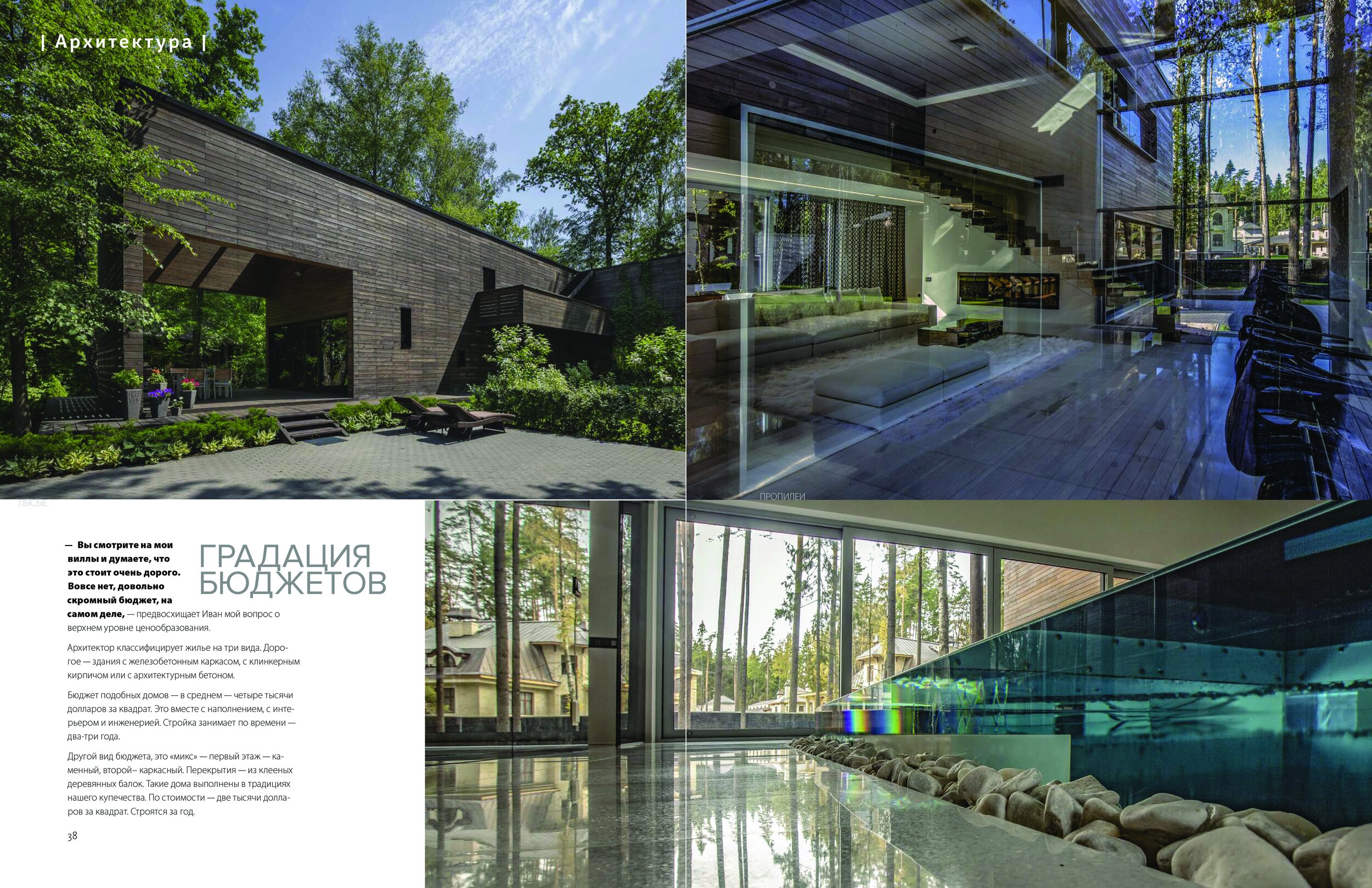

GRADATION OF BUDGETS

‘You look at my villas and you think they are expensive? Not at all, it’s actually quite a modest budget.’ Ivan then proceeds to explain his three tiers.

The first tier is the most expensive – these are buildings with structural concrete, architectural concrete and clinker brick. The cost for these, on average is around 3,000 – 4,000 USD per sqm. This includes all infrastructure, services, interior finishes, installations and furniture. Time wise, these buildings take two to three years to complete.

Tier two is a mix, where the lower storeys are masonry and the upper are timber frame, with glue laminated beams used for the floors. This idea of a structural mix dates back to our ancestors, the Russian merchants. They cost is 2,000 USD per sqm and take one year to build.

Lastly, tier thee is a full timber frame building. This is the most affordable option and only takes six months to complete. ‘If the house has two storeys, it becomes like a living organism, it moves and it can creak a little’ – remarks the architect about the particularities of timber frame houses. ‘But really, the materials themselves are not as important, they are a means to an end. You can even use compressed hay if you really want to. I had a small log cabin with a sauna in a place called Viyazma, that I built myself. This was at the beginning of my professional career, so it was in the style of Vasnetsov, traditionally Russian. It had a big, old fashioned, sloping roof with large overhangs and gables. Some workmen helped me with the main structure and then I did the rest myself. The roof appeared to be floating over a big flax field with blue flowers. One of the partition walls that I built was timber frame and this was the turning point – I understood what to do and started to build timber frame houses.’

Even for the smallest budget, Ivan can offer a solution. ‘Like in that old joke,’ – he explains ‘where the changing room is across the road from the sauna. Except this is not a joke. Your whole plot of land is your home, so you can build several modules or separate rooms – the bedroom, the kitchen, the bathroom, the sauna can all be separated out into individual buildings. Only then do you truly begin to experience nature and can become one with it. This strategy, in the long run is less cost effective and also less energy efficient. However, if a full house is too much to handle all at once and you run the risk of having to freeze the works, it’s much better to split your task into manageable chunks.’

TEXT: YLIYANA OLXOVSKAYA

PHOTOGRAPHY: OLGA ALEXEYENKO

sasha.shalmina@gmail.com

(+44) 747 206 3877